Good ancestry

Actively involving the future in today's choices

Water policy makers must be mindful of future generations in the choices made now, because they often have an impact for generations to come. In the context of good ancestry, it is important to avoid passing on to future generations. The Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, Rijkswaterstaat and the National Delta Program have appointed a Future Ambassador in the person of Mare de Wit to better involve today's young people and tomorrow's residents in policy and decision-making on water and climate adaptation.

De Wit started at Rijkswaterstaat in 2020 as a climate and future-proof water management consultant. "At the time, I was drawing and calculating the future water system, taking into account energy transition, climate change, et cetera. All with an eye for the long term. What struck me at the time was that some of the choices made were not always in line with the direction we want to move in the long term. As a result, problems were being pushed into the future. I began to advise on this more and more often. In that capacity, I was appointed a year and a half ago as quartermaster to clarify the transfer of our choices to future generations. To this end, I set up the project Future at the Table. Together with a group of young professionals and experts, we looked at how we could make our ambition tangible in existing processes. That led to the report 'The Future at the Table' with concrete tools that help prevent policy being passed on to future generations."

Three 'bosses'

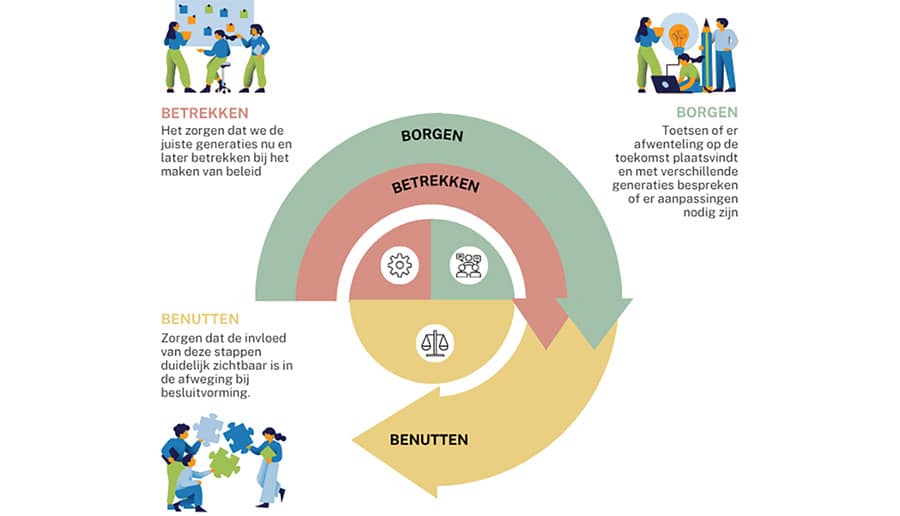

In April this year, De Wit was appointed Future Ambassador for Water and Climate Adaptation. She fulfills that role on behalf of the Delta Commissioner's staff, the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management (Directorate General for Water and Soil), and the Department of Public Works. Sounds strange perhaps that she has three "bosses," but on reflection it actually makes perfect sense. "The Delta Commissioner prepares policy and provides the right information together with the Delta Program partners, based on that the minister makes the decisions and Rijkswaterstaat executes those decisions at the national level. That's the structure, so in that sense quite clear," says De Wit. "My main role for the next two years is to actually implement the methodologies we describe in the report. We all have a responsibility toward the future. With the future at the table, we try to clarify the scope of our impact as consultants, officials or other clients. And to do so, we have formulated three steps: involve, secure and utilize. With each step comes a concrete instrument as a tool."

Expiration date

In the first step, you're going to look at how you involve future generations in your plan, says De Wit. "To do that, it's important to understand the expiration date of your plan. Suppose you are going to work on a new housing development that has to be completed in 2040. If all goes well, it will still exist in 2140. How many generations will you touch, and in what way can you bring those generations into the process now? One way to do that is with the Japanese methodology Future Design, a kind of role-playing game in which you put yourself in the shoes of an inhabitant of the future and enter into conversation with colleagues from here and now. And so there are countless other tools for determining the interests of future generations."

Generation key

In step two, you're going to secure these interests in your plan. "It is quite difficult to secure interests of someone who does not yet exist," De Wit rightly states. "But you can assume that certain needs - reflected in Maslow's pyramid, for example - of future generations are pretty much the same as those of today. We also see this in the approach around broad prosperity, which describes 11 indicators that people need to thrive in a society. In order to safeguard future interests, we have drawn up the generation test, in which you can assess on the basis of these indicators whether a generation is going forward or backward on these themes. And so you can test whether your plan is going to cause problems or create opportunities in the future." The generation test alone, however, is not sufficient to safeguard all interests. De Wit gives an example: "In addition to the generation test, step two therefore also contains the generation discussion to discuss dilemmas from the test, and whether we find the degree to which we are passing on acceptable. If the new residential area is built in a deep polder and the generation test shows that the costs of the project will increase dramatically after 2050, because a pumping station has to be built, we would discuss during the generation meeting what responsibility we have for this, and whether we could, for example, set aside some money now. That kind of thing you discuss in a social dialogue, the generation conversation."

Finally, the third step is leveraging the future at the table. "If you make a decision and start implementing the plan, explain in easy language the way in which you are passing on to the future and what the motives are. Think of it as a piece of stewardship that you express in a decision," clarified De Wit, who now wants to follow through. She will work at the three organizations to encourage good ancestry in decisions. "In addition, I hope that other people in different organizations will take ownership of the theme as well; in principle, everyone can work with it, within any domain and any type of organization. After all, we are all responsible for the future!"