The Pen | Getting rid of rainfall in a normal, physical way is becoming unaffordable

The above statement may come raw on the roof, I realize. With this statement, then, I certainly do not mean to say that what is being done now to dispose of stormwater is futile. Something must be done and all efforts help. However, the climate issue is there and we will only get more and more intense rainfall, on a more frequent basis.

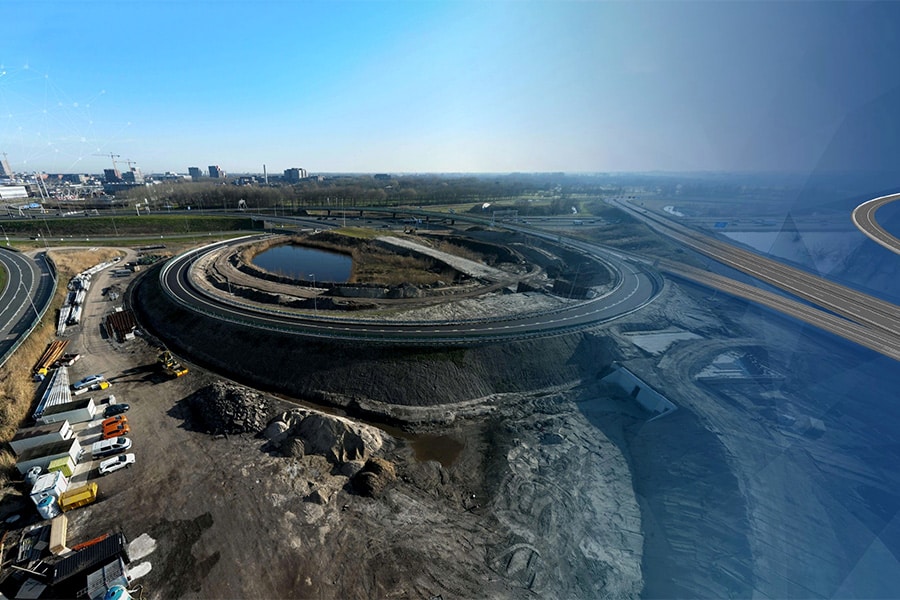

Urbanization has increased dramatically in the Netherlands over the past 25 years. In metropolitan areas, there is simply too little natural surface area that allows for sufficient infiltration to allow water to drain naturally. The sewers are not up to the task, and building new drainage facilities in cities is no easy task. Going ahead with even more large infiltration systems, (pump) wells, double drains et cetera to use them to deal with the future problem requires opening up entire streets and residential areas. With the busy, underground infrastructures then encountered, it becomes difficult to create space. Not to mention the infrastructural above-ground chaos that will ensue. Should we perhaps accept that in the future we will have water at ground level and no longer have a guarantee of dry feet?

Traditional thinking must be broken

Fortunately, much is being done in the Dutch civil engineering sector to address the increasing flooding. While there is talk of innovation, it is usually based on building on known solutions. The question that then arises is whether traditional thinking is going to save us. A question that also plays a role at Nering Bögel and to which we do not have a unanimous answer. After much brainstorming, the idea for Waterquest was born. Based on the philosophy that we need to get bright minds thinking, who are not yet "contaminated" by traditions. Students who approach the problem from different disciplines from directions previously unknown to us. By investing in Waterquest, we are investing in a safe future for all. This is about generations and no longer a quickly calculable "return on investment." After all, the issues can no longer be monetized. If only it were that easy.

The outcome is a well-nigh utopian idea

When, as mentioned, you present a problem to thinkers who are not bothered by old patterns, you can expect an outcome that appears utopian to old patterns of thinking. There is only one way, the results of Waterquest show: we must prevent the rain from coming down where we don't want it. "How then?", I hear you thinking out loud. You can do that by starting from the principle that you can do anything to get to that result. Just imagine that, with unorthodox measures, you can prevent 250 liters of water per second, per hectare from coming down in Amsterdam in a rainstorm that lasts not the normal average 6 minutes, but 30 minutes? (Because those are the hard figures) That would completely justify a revolutionary solution, wouldn't it?

The solution lies in influencing rain clouds in a low atmospheric pressure area. Can we soon move them, better said, direct them by increasing air pressure? Or can we cause saturated clouds to empty before they reach a city by emitting vibrations? That's what we're going to explore with Waterquest. Also the legal aspects involved, because who do we then charge with the rainfall?

More realistic hypothetical solutions are also being explored. For example, the alternative disposal of domestic wastewater so that existing sewers are used only for the transport of rainwater. Or deploying catch basins that fill capsules with rainwater, which are then sent as "tube mail" at a speed of 300 km per hour to areas where the water can be discharged without harmful effects.

The moral of the story: we will have to start preventing the rain from falling in unwanted places. Prevention is the motto, because cure is actually already out of the question. Because this approach does not generate direct income, we will have to rely on social commitment within the infrastructure sector. This requires cooperation. It starts with a cup of coffee and a good conversation with an open mind. You are cordially invited, at this.